MIAMI - The Florida Senate has retreated from its controversial plan to punish college students who choose majors that "do not lead directly to employment" by reducing their scholarship amounts under the state-funded Bright Futures program.

But as the Legislature grapples with a budget deficit brought on by COVID-19, Bright Futures is still in danger of cuts, after being partially restored only a few years ago.

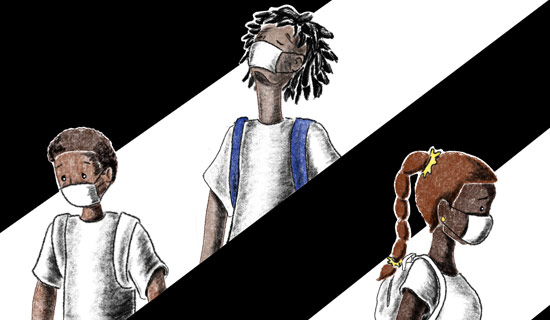

When lawmakers have slashed Bright Futures during past difficult budget cycles, Black and Latino students lost out the most. Some Democratic lawmakers are trying to keep that from happening this time around — especially since students of color have been more affected by both the health and economic crises of the pandemic.

"We need to look for ways, through policy, to not only make sure that students of color aren't once again absorbing the lion's share of the negative consequences of COVID, but also that we are incentivizing them to finish the degrees that they've already started," said Rep. Carlos Guillermo Smith, a Democrat from Orlando.

When Smith was elected to the state House of Representatives in 2016, he became the first out gay Latinx member of the Legisature. He credits Bright Futures for that.

Smith attended the University of Central Florida in the early 2000s with the help of the second level of Bright Futures, which covered 75% of his tuition and fees. The top tier of the scholarship covers 100% of tuition and fees, plus a $300 stipend each semester for books.

"For me, it was the difference between going to a state university and not," Smith said. "I wouldn't be a member of the Florida House of Representatives had I not had access to the Bright Futures scholarship."

But if Smith were a high school student today, his SAT scores wouldn't have made the cut. After the Great Recession, the Legislature made the scholarship harder to get. That way, the state wouldn't have to pay for as many students to go to college.

“Had today's academic standards been in place for Bright Futures, where they are right now … I would not have qualified," Smith said.

It's not just a hypothetical. When the eligibility requirements were tightened, thousands of non-white and low-income students lost access.

Jarrett Gupton, an assistant professor of education at the University of South Florida in Tampa, said that's not because those students didn't deserve the scholarships. It's because many didn't have a fair shot at them.

"If you don't have equitable textbooks, equitable resourcing, equitable teaching staff," Gupton said, "you're going to get inequitable outcomes."

'Blown away' by scholarship inequity

During this year's first meeting of the state Senate education committee, Vice Chair Shevrin Jones asked a representative from the Department of Education for a racial breakdown of students who have received merit-based financial aid, like Bright Futures scholarships.

“Do you know the makeup by race and ethnicity of the recipients in the state of Florida?" Jones, a Black Democrat from West Park, asked the official.

He was "blown away" by the answer: Only 6% of students who received merit-based aid in the 2019-20 academic year are Black. According to the latest federal government data, Black students account for 17% of undergraduates in Florida. Hispanic or Latino students are also underrepresented among Bright Futures recipients, but not nearly as dramatically.

Jones, a former high school science teacher, has advocated for increasing the state's investment in college financial aid based on need instead of merit. Merit-based scholarships are inherently inequitable, he argued, because the measures used to determine eligibility — like grade point averages and standardized test scores — are often influenced by prejudice baked right into our public schools.

“There's no equity in our educational system for students who are Black or who are Hispanic," Jones said.

In recent years, Jones has sponsored a bill that would create a new program called the Sunshine Scholarship — what's known as a "last dollar" award. After a student applies federal aid or any other scholarships they recieve to their college costs, the state would pay the rest: the last dollar. Similar programs exist in other states, like New York and Tennessee.

Smith, the representative from Orlando, has also proposed alternatives to Florida's current financial aid offerings.

In 2017, he sponsored the “Restore Our Bright Futures Act,” which would have lowered the minimum SAT and ACT scores required for the scholarship. It never got a committee hearing.

That same year, though, the Legislature did restore some Bright Futures funding. Delivering on a chief priority of then-Senate President Joe Negron, lawmakers reinstated payments of 100% of tuition and fees, plus a $300 stipend for books, for recipients of the program's top tier. The award had been cut over the years.

Smith said lawmakers should have focused on Bright Futures’ second level, which covers many more non-white and low-income students.

“The lopsided investment that we have here towards those at the top, who already are less likely to need assistance in paying for their college education, I think, is a mistake," Smith said during floor debate in April 2017. "And that’s why I’m voting no, and I urge you members to do the same."

Last year, Smith carried a bill that would have allowed undocumented immigrant students to access state financial aid programs, like Bright Futures, and now he’s focusing his efforts on getting that $300 stipend for books for all Bright Futures recipients — not just those at the top level.

'There is nothing that's off the table'

The Florida Legislature has a history of moving the goalpost for Bright Futures. If it's harder to qualify for the scholarship, fewer students are eligible, and the program is cheaper.

State lawmakers say changing the eligibility requirements has nothing to do with race. But the data are the data: The last time it happened, the number of white students who qualified dropped by half — while two-thirds of Latino students and three-quarters of Black students no longer qualified.

Once again, legislators are faced with making cuts to balance the budget, given the economic toll of COVID-19.

The Bright Futures proposal currently under consideration does not change eligibility requirements but would eliminate the guarantee that the scholarships cover 75 to 100% of college costs. Instead, the awards would be prorated based on whatever amount the Legislature decides to allocate each year, a move that makes the scholarship even more vulnerable to lawmakers' whims during the annual budget cycle.

“With the type of budget shortfall that we have, there is nothing that's off the table," said Rep. Rene Plasencia, "and Bright Futures is definitely something that's under consideration."

Plasencia is a Hispanic Republican from Orlando and chair of the higher education budget committee in the House. He taught government and coached track and cross country for 15 years at Orange County's Colonial High School, where only about 10% of students are white.

When asked if the Legislature would take steps to ensure students of color were not disproportionately impacted by any potential cuts to Bright Futures this session, Plasencia said: "We don't want to make exceptions because we feel bad.”

Plasencia said rather than focusing on scholarship eligibility, the Legislature should address systemic problems like poverty or language barriers that contribute to the achievement gap between students of color and their white peers.

“If there's an issue with Bright Futures, then Bright Futures isn't the only issue," he said.

Jarrett Gupton, the education professor at USF, said Plasencia's rhetoric suggests that students of color aren't as deserving of scholarships.

"That myth that we're continuing to fund the most meritorious through Bright Futures without looking at the broader context … really leads to a very false narrative," Gupton said.

The false narrative, he said, is that students who have the SAT scores, the grades and the volunteer hours to qualify for the Bright Futures scholarships are naturally smarter or work harder.

The societal ills of racism and classism permeate schools, Gupton said, and the result is that students of color and low-income students often have to work a lot harder to perform at the same level as their peers with more advantages.

While schools that serve a majority of Black or Latino students or low-income students often get less funding, it's not just about a dearth of resources, Gupton said. It’s also about attitudes.

"It's sort of a self-fulfilling prophecy," said Gupton, who is Black. "If we believe that students of color will struggle to learn or can't learn or can't perform at high levels, we teach down to them. We don't provide them with the best curriculum. We don't provide them with the best funding. And then all of a sudden, lo and behold, their scores are lower than, say, their white upper income peers."

'Am I smart?'

Going to college with a Bright Futures scholarship was Maricarmen Salablanca’s “main goal” in high school.

Salablanca had the GPA and the volunteer hours she needed to get her tuition and fees paid in full under Bright Futures.

But “it was just one Saturday morning that erased all of my accomplishments," she said.

She couldn't reach the SAT score she needed for even the second, less generous tier of the state-funded scholarship. She missed it by just 20 points.

“I actually took it really hard on myself. I started questioning, like, 'Am I smart?'" Salablanca said. "I just started going off this deep end of like, 'I'm not smart. I can't get this. I don't deserve it.'"

Salablanca, whose parents are immigrants from Nicaragua, went to Coral Reef Senior High in Cutler Bay. It's far whiter and far more affluent than the average school in Miami-Dade County.

She said many of her classmates’ families paid for test prep that hers just couldn't afford.

“So I would see them be able to get an amazing score on their first try," she said. "Meanwhile, it took me a couple of times after studying and studying and studying, but not having the same tutoring that they received.”

Many of her peers also had parents or older siblings who had taken the SAT themselves and could help them prepare for it. Salablanca’s mom finished high school, but her dad didn't, and only one of her two older sisters did. None of them went to college.

“I had no idea what the SAT was," Salablanca said. "My sisters never took it, and my whole family doesn’t even speak English.”

While not getting a Bright Futures scholarship made her doubt herself, Salablanca "kept pushing" and found success another way. She graduated from Coral Reef in 2018, and she ended up getting a different academic scholarship to UCF.

At 21, she’s about to graduate a year early to head to law school. First, she's completing a competitive semester-long internship working for Smith, the state representative.

And as the first one in her family to pursue higher education, Salablanca will be able to offer her niece, a recent high school graduate, something she didn't have: an informal college advisor.

"We talk at least once a week," Salablanca said. "She has me to lean on, thankfully."

Funding for “Class of COVID-19” was provided in part by the Hammer Family Charitable Foundation and the Education Writers Association.