FORT LAUDERDALE — Since the start of the pandemic, nearly 800 students in Broward County Public Schools — the state’s second largest district and the sixth largest in the U.S. — have completely stopped going to school. They haven't logged on to virtual classes or shown up for in-person instruction. Thousands more have racked up chronic absences.

“That’s where we have to hit the pavement and go to the homes and knock on those doors,” said Lilia Francois, a social worker with the Broward school district.

Her job during the pandemic now includes finding students who miss enough school to set them back. By the time Francois gets behind the wheel, a school has tried everything else to locate the child missing from class. The student’s teacher and then the guidance counselor tried calling parents or guardians. Then school staff members reached out to siblings, cousins or classmates who might know where the student is.

One windy day in December, Francois hit the pavement to knock on the door of one student and her mother, whose last names we’re not using, to protect the family's privacy.

“To be honest, I feel badly about this, because this [long absence] is really affecting her,” María, the mother, said in Spanish about her daughter. Marjory should be a high school sophomore, but she has not been to class since March, when school buildings shut down to stop the spread of the coronavirus.

Before finding María and Marjory here, Francois had gone to a different house in Fort Lauderdale, only to find out that the family no longer lived there.

María said she had been struggling to find a stable job and housing.

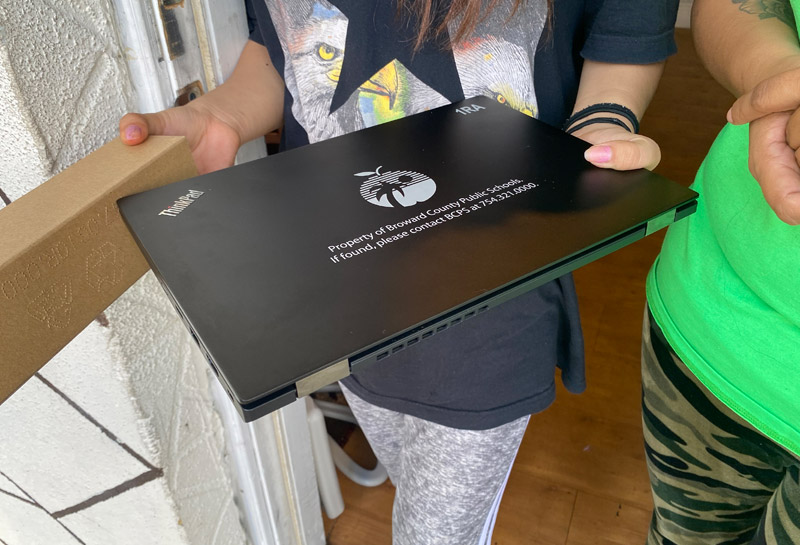

Marjory “hasn’t had the computer,” María said, adding that she hadn’t been able to afford steady access to the internet throughout the pandemic.

“That’s where I come in, that’s where I come in,” Francois jumped in.

Francois handed Marjory a laptop, and as they stood in the doorway of the family's home, they went over Marjory's class schedule and how to use the online learning system, called Canvas.

“If you’re interested in that, we have a lot of clubs, and they’re doing things online, so you still can participate in after-school activities while you’re home,” Francois said.

After Francois gave Marjory all of the technical things she would need, she added a pep talk.

“You’re starting fresh. Whatever happened last quarter, today is a brand new day for you,” Francois said. “You see all these people in your corner? They want you to succeed!”

Marjory's expression changed. She seemed hopeful.

“It’s exciting because, you know, I could start school again,” Marjory said. “Finish high school ...” Her voice trailed off.

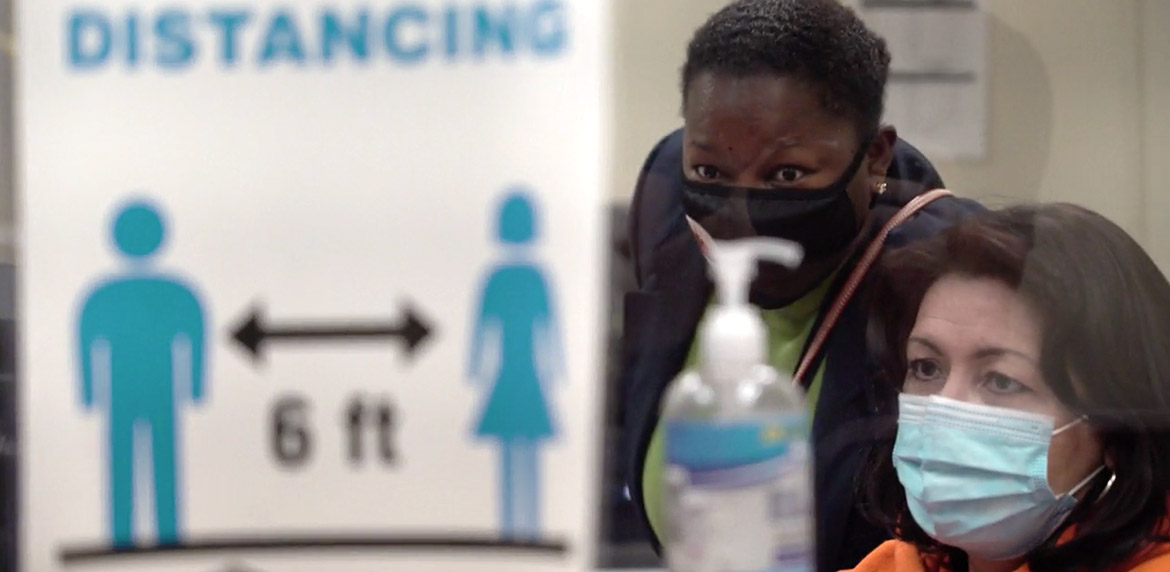

Even students who have been attending classes online are falling behind. Broward County Public Schools Superintendent Robert Runcie told school board members during a Jan. 20 meeting that the district has identified 59,000 virtual students who aren’t making enough progress academically. The district sent letters to those families asking them to consider returning their children to school for in-person classes, as was required by the state. Out of those 59,000 students, Runcie said 84 percent are Black and Latino. More than two-thirds are low-income students. Nearly a quarter have disabilities.

“We’re seeing significant upticks in students with failing grades,” Runcie told WLRN. “It’s gone from 4 percent to 11 percent at the end of the first quarter. Habitually truant students, those with 15 or more unexcused absences, rose from 1,700 to over 8,200.”

“Families and students are facing lots of barriers and challenges with housing instability,” Runcie said, adding other issues to the list: Some households include family members who are sick and parents who work tough schedules. Often, families struggle to buy enough food or afford child care.

“There’s a lot of need out there," he said.

Like students facing these challenges, the district’s social workers need support, too. Lilia Francois has a group of fellow social workers she turns to for advice and encouragement because they see many difficult situations.

Francois' home visits are as much a wellness check as a chance to get a student back in school. “We want to make sure that they’re OK,” Francois said.

She knows what can happen if they're not OK. Francois has been with the district for more than two decades. She pursued this work to help young people after starting her career in criminal justice, where she found that it was often too late to help them.

“I was really tired of seeing young kids coming to jail, and it wasn’t juvenile, but they were being tried as adults,” said Francois, formerly a corrections counselor in Miami-Dade County.

Francois saw a pattern of kids who didn't graduate from high school and had a harder time finding well-paying, stable jobs. For them, joblessness and desperation sometimes led to run-ins with the law.

“That is my why — even if I prevent one kid from going into that system, I think it makes an impact,” she said, humbly. “Maybe a little.”

More than a month later, Francois said she's still trying to get Marjory back in school, but as of late January, she hadn't shown up.

“I have to say that is a unique case. That has not been the situation, where kids have not logged in since March,” Francois said. “We’re not sure where the breakdown happened."

It may be an extreme case, but it's not the only case of students missing a lot of school. Recently, she visited 18 homes in three days.

Melissa Harmon, David Diez and Sergio Figuera of South Florida PBS and Caitie Switalski Muñoz of WLRN contributed reporting for this story.

Funding for “Class of COVID-19” was provided in part by the Hammer Family Charitable Foundation and the Education Writers Association.