MIAMI — One of the promises Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis made to Floridians in his State of the State address this year explicitly pit his administration against local elected officials in every county of the state.

"We will not let anybody close your schools," DeSantis said during the March 2 speech at the Florida Capitol.

The "we" of the DeSantis administration includes his education commissioner, Richard Corcoran, who last fall ordered districts statewide to reopen school buildings for students whose families chose to return. The "anybody" is school board members, who, per the state Constitution, "shall operate, control and supervise all free public schools within the school district."

Despite school board members' constitutional authority, for years the Florida Legislature has chipped away at the once-sacrosanct ideal of local control in public education, one piece of legislation at a time. That was especially true when Corcoran served as the powerful Republican speaker of the Florida House. Now that he is state education commissioner, he has used his position to force one of the biggest battles yet over who's in charge of public schools: a mandate to open classrooms during a pandemic.

Corcoran won that battle, in both practical and political terms. Schools across Florida are open, and the state remains one of only five in the country with any order in place that requires in-person instruction. A lawsuit over Corcoran's July order — brought by the state's largest teachers union, the Florida Education Association — resolved in his favor.

And while there was little public health data to support the decision when it was made last fall, there is now more evidence to suggest that the risks of in-person school are relatively low, while the negative ramifications of ongoing virtual learning are profound and varied. Florida finds itself in a position of having already done, months ago, what most of the rest of the country is just beginning, nearly a year into widespread school closures.

Still, the state forced reopening on school boards under threat of funding cuts that could have added up to tens of millions in losses for the state's largest school districts.

Broward County School Board Chair Rosalind Osgood said the mandate was more of the same from Tallahassee: an "unfunded mandate."

"If we're going to have an executive order that says we need to open schools face-to-face, we also need to simultaneously have an executive order that says that all persons that work in the school system would be able to receive the COVID-19 vaccination. We need the additional moneys to provide additional wraparound services for our kids," Osgood told WLRN during an episode of The Sunshine Economy. The program was part of the Florida Public Media project Class of COVID-19, examining how the pandemic has affected education for the most vulnerable students in Florida.

"Education is in a crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused even more devastation," Osgood said. "We have thousands and thousands of students that are still struggling, but nobody is really sounding the alarm about it."

Alternatively, Miami-Dade County School Board Vice Chair Steve Gallon III argued the school-reopening ultimatum did not represent an infringement on his authority as a local elected official. School boards had the power to go against the state, he said, while the state also had the power to dock districts' funding if they did not comply.

If the question is whether "there has been a dramatic shift in the state's intervention, I would say absolutely not," Gallon said.

"We embrace very strongly our local authority and our control that we will never, ever, ever, ever abdicate," he said.

Staff members for Corcoran declined or ignored multiple requests for an interview for this story.

Top-down decisions about reopening schools

The tug-of-war continues in the Keys.

The state mandate to keep schools open five days a week for all students who choose to attend in-person classes has been in place for months, but apparently the Monroe County School District has not been following it.

Corcoran sent a letter Friday suggesting the district has not been offering students the option of being in school five days a week and that some students going to classes in person were still being taught virtually, just in the classroom instead of at home.

Since last fall, the district in the Keys has been offering an A/B schedule for middle and high school students, where they come to school some days and learn from home other days. The Department of Education says that won't be tolerated any longer and the district has committed to opening classrooms to all students five days a week by the end of the month, although Corcoran and the Monroe County superintendent are still squabbling over the details.

"This order from the Commissioner of Education takes that decision out of our hands,” said Monroe Schools Superintendent Theresa Axford, in a statement Sunday.

Axford has argued that she made decisions based on the advice of local health officials, which is allowed under the emergency order. She also said Corcoran's requirement would jeopardize the district's ability to maintain safe social distancing, based on guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The conflict mirrors what happened months ago in Miami-Dade and Broward counties — the two largest school districts in the state — when Corcoran compelled school board members to reopen classrooms before they believed it was safe.

School districts in South Florida got a temporary reprieve from the requirement to open schools last August, since the region was then engulfed in a summer surge, and new coronavirus cases were exploding.

By late September, though, time was up for Florida's largest school districts. Corcoran sent letters to both, telling them to open their schools or lose tens of millions of dollars.

"I looked up the word extortion. I wanted to make sure I understood the definition," Broward County School Board Member Patricia Good said during a meeting last October.

"The definition is: 'The practice of obtaining something through force of threats,'" she continued. "This is extortion by the Department of Education. There’s no two ways about it."

Over the summer, the Broward school board submitted a plan to the state Department of Education committing to open schools after the first quarter, in mid-October.

"We have followed our reopening plan to a T," Good said. "They approved it."

But Corcoran went back on that approval. He directed the district to open Oct. 5 instead.

Board members described the action not only as "extortion" but also as "heartless," "ungodly" and even discriminatory, since the board is made up of all women.

Board members openly discussed suing over what they argued was the state encroaching on their power as locally elected officials.

"Do we still have the ability to challenge the state legally regarding their overstepping their constitutional authority?" Good asked during the meeting. "Because if they did it with this, they’re going to do it with something else."

Her colleague Nora Rupert put it like this: "The authority of local-level decision makers, elected officials — this seems to be the new endangered species in the state of Florida."

Rosalind Osgood, then vice chair of the Broward school board, said the board and the state "keep playing this game about local control.

"It’s not their money. It’s our money," she said. "It’s the people’s money."

Ultimately, Corcoran and the school board struck a compromise: a phased reopening that brought students back starting Oct. 9. The lawsuit never happened.

"In hindsight, I don't think it would have made any difference," Osgood said during a recent interview.

"We are where we are," she said. "I wouldn't say that it was the right decision to open schools, but I will say that we're at a place now where we have to do everything we can to catch our students up and get them back into some type of learning environment that's going to help them be successful."

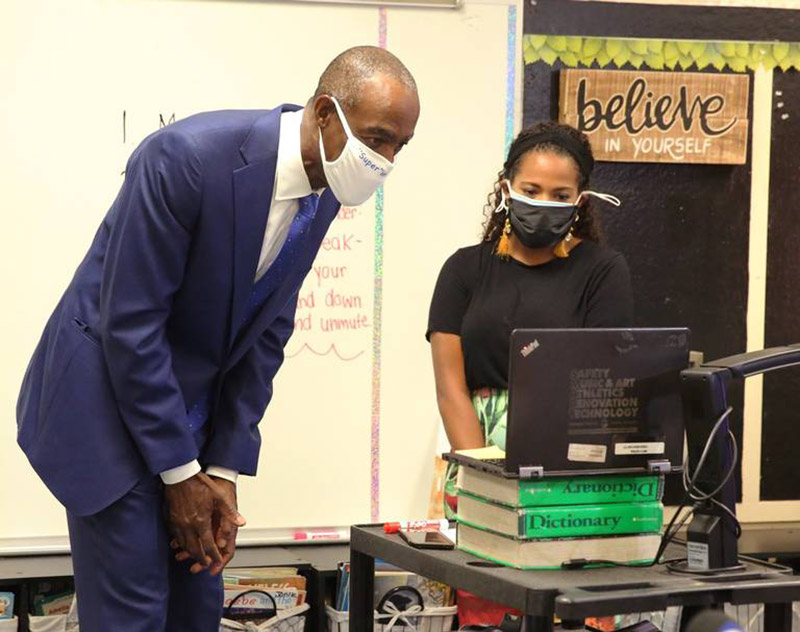

The state also pushed Miami-Dade County Public Schools to reopen Oct. 5, but the situation was different for the state's largest school district.

In its own state-approved reopening plan, Superintendent Alberto Carvalho had committed the district to bring students back on that date — without first getting the school board's signoff. When the school board attempted to push the date back, Corcoran stepped in to stop it.

Steve Gallon III, vice chair of the Miami-Dade board, said the board could have chosen to keep schools closed, but members carefully considered the potential consequences and decided it wasn't worth the risk.

"School districts across the state of Florida — all 67— could have exercised their constitutional authority and said, 'We will not open,'" Gallon said. "But they would do it at the risk of [losing state funding], … which is a real impact to the education of children."

On the 2021 legislative agenda: further limits on school boards

In Feb. 2020, just weeks before the coronavirus would shut down Florida, state lawmakers considered a constitutional amendment that would set eight-year term limits on school board members.

School boards are one of the few elected offices in Florida not already subject to term limits. Elected sheriffs, clerks of court and county property appraisers also are not capped on how many terms they can serve if reelected.

"This is the amazing bill on school board term limits that we discussed yesterday," Rep. Anthony Sabatini, a Republican from central Florida, said on the House floor Feb. 20 last year.

"Is there debate on Sabatini's amazing bill?" said then-House Speaker Jose Oliva, a Miami Lakes Republican. He called on then-Rep. Tina Polsky first.

"It may not be that amazing, after all," said Polsky, a Democrat from Boca Raton. "Basically this is yet another attempt to take away local control."

Polsky's colleague, and another Palm Beach County Democrat, Rep. Matt Willhite, was on the other side of the issue. He was a main co-sponsor of the bill, alongside Sabatini.

Willhite argued it should be up to the voters to decide whether school board members should face term limits — and that's why he supported passing a constitutional amendment. Before it would be final, the change would have to go before voters in a referendum.

"Hopefully in November, the electorate will make the choice. They will decide what goes in our state Constitution," Willhite said then.

The proposal passed the House but died in the Senate. It's back this year, along with another proposed constitutional amendment that would eliminate salaries for school board members. Those salaries are now capped at about $45,000.

The leaders of South Florida school districts see those proposals as directly targeting their power. They also worry, if passed, the bills would block low- or middle-income people from running for office. Plus, they say the bills would make it difficult for racial minorities to achieve representation.

"Any effort to place some limitations either on time served, or on compensation of school board members — I believe that it will have an adverse impact on the equitable and appropriate representation of communities," said Gallon, the vice chair of the Miami-Dade County School Board. He is serving his second term.

Osgood, chair of the Broward County School Board, is now serving her third four-year term.

"If you're not able to get that compensation and you have a family that you have to take care of, you're not going to be able to serve on the school board, because economically you can't afford to," Osgood said.

"These are a lot of the games that we see with public policy that disenfranchise some communities," Osgood said. "The community has a right to elect the person that they feel best represents them in their interests, and it shouldn't be based on economic status."

Funding for “Class of COVID-19” was provided in part by the Hammer Family Charitable Foundation and the Education Writers Association.